How to save a PDF

If you would like to save the page you’re viewing as a PDF document, here are the steps:

- Click icon with 3 stacked dots

/

or

lines to the right of the URL bar at the top of your browser

- Select the “Print” option

- A pop up window like this one should appear, ensure the Destination field is set to “Save as PDF” (this may be a dropdown or “Change” button)

- Click “Save,” then select the location and name for the file on your computer

Protecting the Protectors

Mental health support for first responders should be a top civic priority.

By Tad Simons

Originally published in the March-April 2019 issue of Minnesota Cities magazine

Emergency first responders encounter scenes of unimaginable horror and tragedy on a regular basis. Gruesome car accidents. Shootings and stabbings. Natural disasters. Sexual assaults. Elder and child abuse. Illnesses and injuries of all kinds.

These are all situations that first responders—police officers, firefighters, emergency medical technicians, and other emergency medical services (EMS) personnel—are trained to handle.  But for some, the daily encounter with human suffering and violence can take a serious psychological toll that, left unattended, sometimes leads to mental health problems like depression, addiction, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

But for some, the daily encounter with human suffering and violence can take a serious psychological toll that, left unattended, sometimes leads to mental health problems like depression, addiction, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

These are conditions that can be debilitating and, in some cases, even fatal. Several studies have found that rates of suicide and attempted suicide are higher among first responders when compared to the general population.

The need for support

But many mental illnesses could be prevented—and lives could be saved—if the individuals involved could get the help they need, when they need it. There is a growing consensus among EMS support groups, mental health professionals, public policy specialists—and even first responders themselves—that supporting and maintaining the mental health of those called upon to clean up society’s messes needs to be a much higher priority.

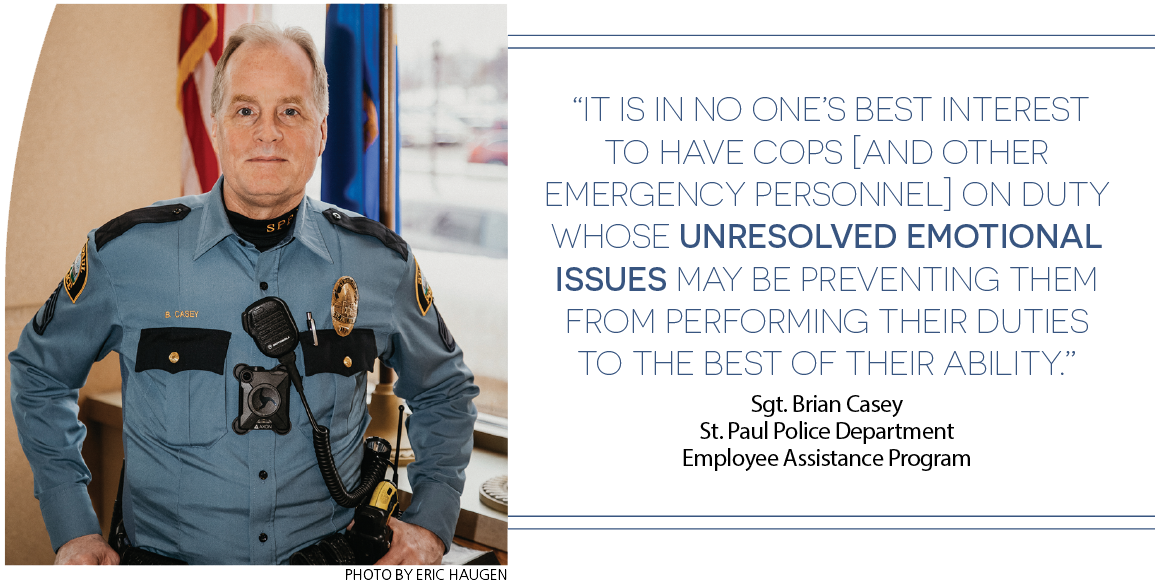

“It is in no one’s best interest to have cops [and other emergency personnel] on duty whose unresolved emotional issues may be preventing them from performing their duties to the best of their ability,” says Sgt. Brian Casey, director of the St. Paul Police Department’s Employee Assistance Program. “And it is in everyone’s best interest to make sure that when an officer needs help, they get the support and assistance they need.”

Casey is a veteran police officer who started his public safety career as a paramedic, and now helps colleagues grapple with the stresses and pressures of police work. In his new book, Good Cop, Good Cop: A Get Healthy, Stay Healthy Guide for Law Enforcement, Casey explores many of the obstacles that prevent police officers from seeking help—from the social stigma of having a mental health problem, to male stereotypes about strength and toughness, to fears that if officers seek help for a mental health issue, they might lose their job.

“Many cops are afraid that if they are honest about their distress, they will lose their badge,” says Casey. “The truth is, what can put them at risk for getting fired is failing to work out their personal problems.” Still, it’s not easy for those who spend their working lives helping people to admit that they might need help themselves. One of the great paradoxes of police work, says Casey, is that the very qualities that make for a good police officer—vigilance, alertness to danger, calmness in the face of enormous stress, etc.—are precisely the qualities that can cause problems in relationships and family life when an officer’s shift is over.

“Cops eagerly and willingly put themselves in unnatural and dangerous situations,” says Casey. “But in order to survive, law enforcement personnel learn how to turn their alarm systems down. They need to be able to hide their stress. But some of the things that are necessary to be a good cop are the same things that can be harmful if they are carried too far into other parts of their life.”

Emotional resilience in the face of tragedy

What Casey and many health professionals advocate is teaching first responders—through workshops, peer support groups, therapy, and even better friendships—to strengthen their “emotional resilience,” and find healthier ways to manage the stress of repeated encounters with traumas large and small.

Emotional problems and their consequences—marital strife, compromised job performance, social withdrawal, and even divorce—tend to accrue over time. Casey calls this the “slow burn of psychological trauma,” and many first responders feel it’s their job to “suck it up” rather than admit to anyone that they are having difficulties. Feelings of loneliness, isolation, and despair can snowball into full-blown depression or worse, but they don’t have to, Casey says.

Sometimes, simply talking to a colleague can help. So can participating in group discussions, or talking to a trained counselor or professional therapist. Toughing it out alone is rarely the answer, however. What police officers and other first responders need to understand, says Casey, is that it is actually a first responder’s responsibility to seek help if they feel their job performance is being compromised by unresolved emotional issues.

Even worst-case scenarios are not hopeless. For example, many first responders fear that a diagnosis of PTSD will end their career. But according to Dr. John Sutherland, director of addiction services at Allina Health, “PTSD is treatable in most people.”

Sutherland specializes in a treatment for PTSD called “prolonged exposure,” in which patients revisit their feared memories and confront situations they are trying to avoid. Many people who suffer from PTSD get better within the protocol’s 10 to 12 sessions, says Sutherland.

One of the trickiest things about trauma, however, is that individuals respond to tragic events in different ways. The scene of a horrible car accident might haunt one first responder for years, but may be experienced as just another day at work for others at the scene. Those who are traumatized may not show symptoms for months or years, during which time they may be performing well on the job but suffering personally, coping the best way they know how.

All first responders need to develop healthy coping skills, says Sutherland, but the goal should be to provide EMS personnel with “more tools to deal with the psychological realities of their profession,” and to de-stigmatize mental health services to the point where those who can benefit from treatment are willing and able to get the help they need.

“In my experience, first responders tend to be reluctant to seek treatment,” says Sutherland, “but once they are in treatment, they respond quite well, because they are motivated to get back on the job.”

Toward a healthier model

Creating a mentally healthy work environment for first responders involves more than just talking and therapy, however. It starts at the top with leadership that sets a tone of support and encouragement, along with effective procedures for managing personnel who may be struggling. It’s also important to have a culture of peer support based on awareness that there are healthy—and unhealthy—ways to deal with emotional strain.

Another factor is educating family members about how to support first responders, as well as what to do if their loved ones are having trouble sleeping or are engaging in what psychologists refer to as “avoidance” behaviors—such as alcohol and substance abuse, risky sexual encounters, emotionally distancing oneself from spouses and family members—that are ultimately self-destructive.

Another factor is educating family members about how to support first responders, as well as what to do if their loved ones are having trouble sleeping or are engaging in what psychologists refer to as “avoidance” behaviors—such as alcohol and substance abuse, risky sexual encounters, emotionally distancing oneself from spouses and family members—that are ultimately self-destructive.

For many years, the League of Minnesota Cities Insurance Trust (LMCIT) has been involved in efforts to address the issue of first responder mental health through workshops, online training programs, and face-to-face outreach.

Two years ago, Casey conducted a mental health session at the nine LMCIT Safety and Loss Control Workshops held around the state. In addition, LMCIT has co-sponsored 15 Mental Health First Aid Workshops, which have also been offered at locations throughout the state.

LMCIT Public Safety Coordinator Rob Boe, a former police officer himself, says, “Public safety personnel should be aware that even if they don’t have full-blown PTSD—if they are struggling with depression, anxiety, alcoholism, or some other issue—there is a whole range of services available through their personal health plan, employee assistance, and other community support services.”

Since 2013, PTSD has been a compensable workers’ compensation claim for many EMS professionals under state law and LMCIT’s workers’ compensation coverage. Ultimately, however, the goal of leadership in public safety should be to help people avoid PTSD when possible and help them recover when it does occur. Because lives depend on it.

Tad Simons is a freelance writer from St. Paul.